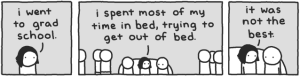

The posts on this blog are told like short stories. Although the collection of posts relates a longer story of my deployment to Iraq, each post can be read independently, without loss of continuity. I wrote them this way to make each one entertaining on its own. One downside to composing my memories as a series of self-contained stories, however, is that some of them inevitably fall to the wayside. They might be too tangential to any one story, or it simply might have been too hard to fit them in. Maybe doing so would have broken the flow of the greater story, or would have just made it too long. Maybe I just forgot. Nonetheless, they’re memories that I treasure, of a time that marked one of the great periods of change in my life. I still tell them during conversations or just when a good opportunity arises.

So here are the bits and pieces that didn’t make it into the stories, but help to fill out the experience. Enjoy.

Wardrobe Malfunctions

It took a while for our command to settle on a stable duty uniform. This is really a problem that can only exist in an organization that is at once so driven by hard pragmatism yet so mired in bureaucracy as the military. Our daily changing uniform directives became both a running joke and a source of unneeded annoyance. At first, we were told to dress is “full battle rattle” – fatigues (BDUs, in Army parlance), helmets, boots and body armor – during all work activities. Many of those early work involved strong manual labor as we worked to build our living and working quarters. Building, demo and digging are hot enough without full battle rattle in the midday of the desert. Next, we were told to work in our PT (physical training) uniform, consisting of a t-shirt, shorts and running shoes (trainers, for the British reader), but to keep on our helmets and body armor. The next day, we were ordered to swap the running shoes for our combat boots, which, while still slightly more comfortable than the first day’s uniform, looked ridiculous bordering on profane (for some shorter people, their shorts were hard to see under the chest plate). The day after that, we were told to go back to BDUs but that we could lose the blouse (what normal people call a jacket). The end of the week arrived with directions to wear BDUs (with blouse) and full armor, but that we could wear our running shoes instead of our combat boots. Tomorrow, said Armstrong, we’ll wear our body armor with nothing underneath and our battle buddy’s PT shorts on our heads. Tomorrow, Rick said, the command sergeant major can wear his rifle up his ass.

The Time They Gave Us Non-Alcoholic Budweiser

I dislike Budweiser. I think that it is a genuinely bad beer. It’s lazy, boring and tasteless and its only redeeming value is that it can be quite refreshing when it is very cold and you are very hot and thirsty. In this way it is similar to cold water, or cold piss, should you be short on other options. One hot day, a bunch of us from ambulance and treatment platoons sat around our trucks during down time on some training event. Someone, Lt Chapman maybe, drove up with an unexpected gift: a case of cold Bud.

Our mouths watered like Pavlov’s dogs and we were bitten by the sense of thirst the second we laid eyes on the beer. The lieutenant told us to dig in and so we did. I looked at my can and saw the two letters “NA” following the usual Budweiser logo. What is “NA”, I asked. Someone else, Brian maybe, read the label a little further. It’s non-alcoholic, he said. This elicited cries of “What the fuck?!” and other angrily disillusioned remarks.

While some of the others shrugged and drank it anyway, I pantomimed a mock firing

squad for my can. It was hot, though and I was thirsty and anyway, we were out there in the desert, a long way from such comforts of home as real beer, so I shrugged too, and enjoyed my Budweiser NA with the others. When I was finished, I had another and watched the sun go down while waiting to be called back to duty.

The Dead

I’ll count myself as fortunate, that I only saw one dead body in Iraq. A truck had driven into a ditch along a road and turned over during a convoy and one of its occupants had died in the crash. As we manned the nearest battalion aid station (BAS), the soldier’s body was brought to us so that a physician could pronounce him dead and initiate the process of paperwork that followed a death. One of our doctors, another medic and I jumped into the back of the truck, where the soldier’s remains had been transported. His body had been draped with a cloth. We pulled it back and I was struck by the man’s doll-like and unhuman appearance. Looking at him, I could not picture him having ever been alive. Such was the wax museum unreality of his features. The doctor quickly checked him out, made his grim pronouncement and the two of us medics began the solemn task of cataloguing his possessions before sending his remains on to Baghdad, from where he would then be flown home.

The Game of Risk

There is some irony to be found in the image of soldiers in an active war zone playing Risk. For us, this game evolved from a good way to pass long hours into a passion bordering on obsession. I cannot overstate this. Because a single game could last for several days, due to the duty shifts of everyone involved, we actually made a separate guard roster to make sure that no one grew too tempted to alter the board between rounds. Remember that Seinfeld episode, where Kramer and Newman get so passionate about their game of Risk that they even take it onto the subway? We lived that episode. One of the biggest jokes in the episode involved the phrase “the Ukraine is weak.” The Ukraine might be challenging to defend in Risk, but it pales in comparison to Southern Europe, which on the Risk board, is mostly Italy.

One of the Risk regulars was a guy named Grizzante. If his name doesn’t give it away, he traced his family heritage to Italy. He was extremely proud of this heritage and his strategy in Risk was consistently to take Southern Europe/Italy as quickly as possible and use that as his base to launch attacks elsewhere. This might literally be the single worst strategy possible in Risk. Grizz lost every single match and as this wore on, we teased him about it more and more. “Eetaly is veak!” we shouted with glee, as Grizz fumed, arms crossed, his tattoo of Italy prominently displayed down one tricep.

One night he had enough. Someone at the table took out Grizz’s last army within only a few rounds. Amidst jokes and laughter, Grizz shouted “fuck this game anyway!”, flipped the board over and stormed out of the ambulance depot quarters, causing peals of laughter from the group inside. Grizz, come back, we called and after a minute, he did.

Captain Dickhead Proves Unhelpful

I’ve mentioned in past posts, that the soldiers in my unit did not have an entirely nurturing relationship with Captain V, our commanding officer. Cpt. V once accompanied one of the convoys that Dustan and I worked on. On the way back, while driving down a stretch of road the cut through farmland, we heard the ping of bullets glancing off kevlar plating. There weren’t many, but someone was clearly taking shots at our convoy. The radio lit up with chatter about what various people could see, how many shots were being fired, which vehicles they hit. Sitting in the passenger seat, I did what any normal person might do and pressed myself as far back into my seat as I could go in an effort to take maximum advantage of the thin armored lip of the door frame. It was pretty clear that this was just somebody hidden in the distance hoping for a lucky shot, rather than the beginning of an ambush. Drive through it, the convoy commander ordered over the radio. This was standard operating procedure for us. The attention drawn by stopping an armed convoy could easily turn a relatively simple situation like this one into something much greater. The coordinates of the incident were called in to be investigated by other units.

Moments later, however, the convoy was at a full halt. The shooter actually did manage a halfway lucky shot. The victim was our rear passenger side tire. Dustan and I jumped into action. We grabbed the tire change kit, chocked the wheels and started cranking the jack. Again and again, the weight of the ambulance pushed the jack into the loose soil of the road. Growing concerned with our exposure and loss of time and not enjoying our place at the center of attention, we finally found a more solid spot to place the jack. Once up, Dustan and I put all our energy into changing the tire as fast as possible. Cpt. Dickhead invested his energy int superfluous advice. “Put your weight into it!”, he shouted, smiling. It cost Dustan and I most of our strength to loosen the lug nuts. The jack still wasn’t optimally high, owing to the softness of the earth, which made the lug wrench hit the dirt hard with the force required to loosen the nuts. Our knuckles hit the dirt with it and tore open. We swore and kept cranking.

Holy shit, get a load of this, said Dustan. We had just swapped off on wrench duty. He stood lookout, while my knuckles softened the impact of the wrench striking earth. That motherfucker is taking pictures of himself.

This was 2003 and they weren’t called selfies yet, or if they were, we weren’t hip enough to have known.

There he stood, Cpt. Asshat, wandering around the dirt off the road like a complete and happy idiot, posing for selfies with his weapon slung across his back. Not a care in the world. Unbelievable, I said. Motherfucker, we said. Piece of shit. Come on you two, put a little elbow grease into it! came the cry from Cpt. Boy Wonder, reverberating across the desert.

Fueled by anger and resentment, the elbow grease paid off and we returned to our base with a new story to tell.

Aftermath of an IED and Reflections on Memory

Our convoy missed a turn-off and we had to back-track a bit, losing some time. Shortly after turning onto the road we were supposed to have taken, we came across a sobering sight. The charred and still smoldering remains of a US truck, the open-back kind often used to transport troops, lay to our driver side. A chopper could vaguely be made out, rapidly disappearing in the distance. I never got the story about what happened there, or which unit was involved. It was left to our imaginations and meager detective skills to infer the recent past. My guess is that the truck was hit by an IED.

Given how recent the scene looked, Dustan and I had the sobering thought, had we not missed our turn earlier, that same scene would have played out with a slightly different cast. Someone else would be driving by the wreckage of one of our vehicles, maybe even our own. We slipped into silence for a while as we put miles between us and the carnage.

You know, I said, all this is so fresh right now, but sometime in the future, we won’t remember it the way it happened. Not just today, but all of this. It will all change for each of us, over time. There’s nothing much to be done about it, that’s just the way memory works. It’s just strange to think of right now. Yeah, he said, it really is. I guess we’d better write it down.

It took almost thirteen years to finally begin doing that, and now you’re reading my corrupt memories of that year.

Desert Vasectomy

Colonel Adams stepped into the ambulance depot one day with an unexpected offer.

Who wants to learn how to do a vasectomy?

A quick glance, a few nodded heads and four or five of us found ourselves in one of the treatment rooms in our battalion aid station (BAS), gathered around a middle-aged and mustachioed soldier laying on the room’s bed. Time has erased the reason that this soldier opted to get a vasectomy on an Army post in Iraq, but if nothing else, it illustrates our distance from most wartime action.

We assisted Doc Adams in setting up a sterile field and readying the needed instruments.

This is a very quick and simple procedure, Doc Adams said. I’ll talk you through each step as I perform it and then you can provide more of a hands-on assist in the future. Sounds good, sir, we replied.

This was actually poor planning on his part, as the first step in the procedure involves injecting local anesthesia into the scrotum, or in layman’s terms, stabbing the balls with a needle. If just reading that elicits some sympathy pains, imagine watching it happen in real time.

How’s it going up there, Doc Adams asked the patient. Adams looked up at the patient, who’s face was literally as white as a clean sheet. Doc Adams followed the patient’s gaze to my own face, which was probably a mask of fear. Man, you gotta wear a surgical mask or something, if you’re gonna be in here, Doc Adams said to me.

I nodded, took a deep breath and got the mask.

Going 15 in a 12

During those final days in Kuwait, while we were getting everything ready to be packed into a ship for the voyage home, Dustan and I drove our ambulance through a large and largely empty field on Camp Arifjan. In the side mirror, we saw a hummvee marked “MP” (military police) quickly pulling around us. When the other truck came alongside, the MP in the passenger seat motioned for us to pull over, which we did.

The MP, a captain, jumped out of his vehicle and ran to our driver side window. What took place next felt like a demented Monty Python sketch, or an angrier scene from Super Troopers.

Do you know how fast you were going? the MP asked.

About 15, Dustan replied.

That’s right, about 15! You were going 15 miles per hour.

A pause, in which neither Dustan nor I knew what to say.

Do you know what the speed limit is here?

Sir, to be very honest, I didn’t know that there was a speed limit right here.

It’s 12 miles per hour! The speed limit is 12 miles per hour! You were doing 15!

Our odometer doesn’t measure 12 miles per hour. It lists increments of ten.

Are you being smart with me?

No, sir.

You’re telling me that you can’t tell 12 miles per hour on your odometer?

Sir, I’m telling you that 12 miles per hour isn’t a real speed limit and that going 3mph over it is meaningless.

WHO’S YOUR FIRST SERGEANT? WHO’S YOUR COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR?

We gave him their names.

I’ll see you both tomorrow for some extra duty. I hope you like digging ditches. This’ll teach you to be disrespectful. Don’t think I won’t get in touch with your First Sergeant!

We parked our vehicle at our company headquarters tent and decided to tell our First Sergeant ourselves that he should expect an angry call from the world’s most unbending MP. We related the story to him and unsurprisingly, he got a good laugh out of it. I can’t wait for him to call, he said, I really hope he does! I’ll fuck him up!

To add further insult to the poor MP, that was our last night in Kuwait. The next day, we almost died loading our vehicles onto the boat and flew out of country.