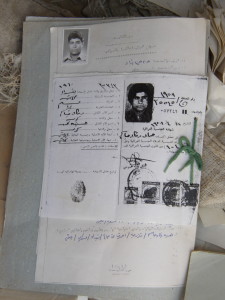

Our first task at TQ was cleaning up the detritus of its former inhabitants. Originally built by the British RAF after WWII, then used by the Iraqi Air Force, its ruins were littered with clues of its former occupants. From the look of it, it had been a mess for long time. I don’t know much about its use, if any, immediately prior to our occupation. It had been bombed during the first Gulf War in 1991 and as far as I could tell, little appeared to have happened since. When we set foot there, the desert was well on its way to reclaiming a collection of old documents, rusted filing cabinets, atropine injection needles, gas masks and a few dried-out combat boots. The chemical warfare paraphernalia and lack of knowledge concerning al-Taqaddum’s recent past put people a little on edge. We sifted through the wreckage, with our own gas masks at the ready, put on edge by the chemical warfare paraphernalia and our lack of knowledge concerning al-Taqaddum’s recent past. It was eerie, seeing only the negative spaces around which people once moved. Empty vehicles, desks and beds. A pair of boots drying in the sand. Gas masks, paperwork, the empty packaging of a dry ration. Being surrounded by personal effects with no people attached to them made me feel like a ghost, an observer to a world that I wasn’t fully part of. If I could only squint my eyes just right, I might see the people, who were surely there, moving about in all the patterns of their daily routines. Except that they were the ghosts, of course, but then I thought that perhaps that distinction lacked any meaning there.

As we developed our base, we installed a shopping and food court area, all run by local business folk. It included a shawarma stand that offered pizza, which we ordered once, while missing the comforts of home. We missed the same comforts after eating it. It wasn’t bad, but the guys running the shop might have only ever seen pizza on TV or in movies. The dough was an unleavened bread, rather like a oversized pita. The sauce was something like a tzatziki without dill and the topping was clearly lamb shawarma, recently cut from the rotating spit of meat in the corner of the stand. It probably tasted fine, although our enjoyment might have been clouded by mild disappointment at the unexpected result of our order.

I got to sample some much better food, thanks to our translator. To my chagrin, I forget the guy’s name. I wish I hadn’t, but there’s nothing I can do about it now. We were together only briefly and when we parted, it was final.

He was a slender man, only a little older than myself and an inch or two shorter. He worked at the battalion aid station (BAS, a clinic/urgent care). He seemed gratified by my attempts to learn Arabic and enthusiastically taught me as many useful phrases as I could learn. Despite doing him the disservice of having forgotten his name, I remember that he had been a university professor and was often asked to act as muezzin, the one who calls others to prayer, because of his singing voice. He began working with us early on, while we were still repairing the building that would become our aid station and we sometimes took lunch together, me eating an MRE and him eating a meal that his wife had prepared for him. Without exception, his meals looked and smelled better than mine. They usually consisted of chicken and an assortment of brightly colored pickled vegetables. After joking about the relative qualities of each other’s food, he offered to bring me in some of his. I accepted. The food on this occasion did not disappoint. The chicken had been roasted and remained juicy as though it had also been brined. The pickled vegetables were delicious. Some of my squad mates warned, half-jokingly, that I should be wary of any food cooked by the locals, this being an ideal way to poison an American invader. I didn’t buy the argument and did not regret the results.

The only danger we were ever in on account of the locals came about from pure human error. This occurred when the ammunition tent caught fire. Corey and I were first up on ambulance duty when the call came in. Corey drove, while I set up the patient compartment. Corey gunned the engine and hit the road. Unhindered by any seat belt, every bump in the road sent me flying into walls, the ceiling and back down onto the floor. “Slow the fuck down!” I shouted. “Sorry!” Corey replied.

As medics, most of our interactions with the Iraqis occurred in our BAS, while treating the frequent and

thankfully always minor injuries of the day laborers. The day laborers who helped build our working and living spaces were hard working and said little. Thinking back on them in the years that have passed, they often blend into images of cowboys from movies about the Old West. There was the old man who was bitten by a scorpion. He wore an epic mustache. Picture Lawrence of Arabia played by Sam Elliot. He walked into the BAS while I was on duty there and showed us the sting mark. His skin, at the site of the sting, burned a deep, angry red. Pus oozed out of it. At no point did the old man show the slightest physical sign of discomfort. How badly does it hurt, we asked. Not much, he replied and then asked for Viagra. We don’t stock Viagra, I told him. It’s not for me, he said, it’s for my wife. It always is, I thought. I sympathized with him, but we still didn’t have any.

I remember one of the translators name was Uday. I remember it being unfortunate because it was the name of Saddam’s son. He loved watching American movies. I think The Last Boy Scout was his favorite. He wrote us a letter when he left telling everyone it was a pleasure working with us and he wished us all well. Hope he is well too.

Thank you! I hate forgetting things like that…I hope he’s well, too.