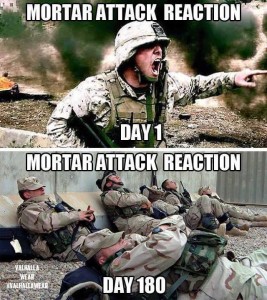

Roadside scene, somewhere near Baghdad.

During one brief period of the deployment, my company was tasked to provide medical support to an infantry unit that manned a small post in a village closer to Fallujah, from which they would send units out on patrols. On occasion, they coordinated with Special Forces units to go on a raid in which they would take various targets prisoner. These prisoners would be interrogated at a short-term holding camp about an hour’s drive away before being either released or sent on. I now assume that they were ‘sent on’ to Abu Ghraib, but this was before the horrors that took place there came to light and if I ever even heard the name, it meant little more to me than the name of any other place in that country.

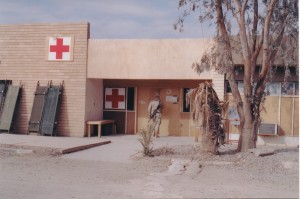

The medics of my unit were needed mainly to man the clinic on their base while their soldiers went out on raids or patrols. We did the same things that we did on our base, pulling sick call duty, guard duty, etc. Once, however, two of us were sent to spend two or three days at the detention camp. If nothing else, I thought that this would provide a break from both the daily routine and my First Sergeant’s unwelcome attention. The detention camp was roughly an hour’s drive from the base, down potholed dirt roads bordered by a mosaic of rice paddies, vegetable plots, grazing areas and the red desert.

Typical Iraqi street scene, as seen from the passenger seat.

We worked primarily during the nights and in my memories, I can now hardly remember the place in the daylight. Interrogations took place during the days. The interrogations were highly controlled environments, in which no one ever suffered an injury that called for our attention. The few injuries we treated were usually small things incurred during raids, often the result of scrambling over broken terrain in the dark, an effort rendered futile by our night vision technology. My partner on this mission, Armstrong, had a slightly different job specialty from mine. Whereas I had trained as a field medic, to spend most of my time working from my ambulance or to be otherwise ‘in the field’, he had trained to work predominantly in a hospital environment. Minor differences aside, we had the same skill set.

On our last night there, we were summoned to render aid to a man brought in from a raid. The soldier who brought us to him told us that the man had a deep gash on the palm of his left hand from having tried to climb through a broken window to escape the raiders. “It’s pretty deep,” he said. “It’s bleeding a lot. I think he might need stitches.”

We brought our ambulance over to where the man was being held. We found him kneeling on the sandy ground, clutching his hand with a burlap sack over his head, duct taped onto him at the level of his eyes. An MP stood guard behind him. We knelt and spoke to him, saying, in a broken pastiche of english and arabic that we were medics and needed to look at his hand. He obliged and treated us to a view of his torn palm. He had thick, meaty hands, the kind made large and hardened by a lifetime of manual labor. True to the first soldier’s description, the cut was “pretty deep”. It was also jagged, looking more like a bullet’s exit wound than anything that might result from a knife edge. We cleaned it up to get a better look at it. This further confirmed that it was a very deep cut, extending through the many layers of fascia and into the muscles of the hand.

Armstrong, who would rather have been fishing.

“Yeah,” I said, “looks like he’ll need stitches.”

“Yup,” said Armstrong in agreement, “definitely.”

We walked over to the back of our ambulance, where one of the items we kept was a sealed, sterile suture kit.

“Go for it,” I said, or something along those lines.

Armstrong snorted and shook his head slightly, “I don’t know how to do stitches. You’re the medic, you go for it.”

“I’ve never thrown stitches,” I replied in a hushed voice, “I’ve only just seen it done once in AIT.” AIT stands for Advanced Individual Training. It is the set of specialist training that soldiers undergo following basic training.

At this point, I was glad to be out of earshot of the guard.

“How have you never learned to throw stitches?” I asked Armstrong. “Isn’t that something you have to know as a nurse?”

“We only ever talked about it. It was something our unit was supposed to train us in. Then when I got out of AIT & jump school, I was tasked to your unit & no one trained me. I thought you had to learn that stuff to be a field medic.”

“Shit! My instructor in AIT just showed us how to do it on an orange, then said that if it was something that we needed to know for our individual unit, that unit would train us.”

“Shit.”

…

“Think we should call for higher level care?”

In many settings, this would be a very straightforward question. As it was, this seemingly simple question required some discussion. As this episode took place sometime during the transition from the dead of night to the wee hours of the morning, calling for higher level care meant waking up a doctor back at the base. Once awake, transport and a security detail would be arranged. Transport could take the form of a humvee, which would take about an hour to drive to us, or a helicopter, which would involve an even bigger operation and would make a decidedly more dramatic entrance. All for a guy with a cut on his hand. It would be like passing out during a job interview and waking to find that two ambulances, a police squad, a fire truck and a SWAT team had been called to the scene. Except in this case, the responders would all be angry.

The motto of the medical profession is “first do no harm”. It serves a guideline for treatment, especially in cases where uncertainty might exist concerning a given treatment. Our interpretation of this guideline on this occasion was that, given the logistical challenges and certain embarrassment of calling for help, we could comply with our ethical obligations as medics by ensuring, thanks to our supply of lidocaine, that even if we did a hack job of the stitches, we could painlessly stop our patient’s bleeding and manage the wound until it could be improved by higher-level medical attention. The doctor at the aid station back on the base was scheduled to come to the detention camp in a day’s time, anyway. At that time, we would be sure to bring the patient to his attention and take whatever reprimands the doctor might have for us in a much quieter environment. This might not have represented the highest level of care possible for an individual, but we felt that under the circumstances, the greatest number of people involved all stood to benefit.

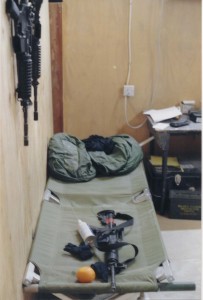

The patient compartment of our FLA, where we kept the suture kit.

With these best of intentions in mind, we broke out the suture kit and began preparing to do medicine. For reasons lost to my memory, it fell to me to actually perform the procedure, while Armstrong stood by to assist, offer moral support, or perhaps distract the guard, as needed. The first thing was to anesthetize our patient’s hand with lidocaine. Lidocaine is what is called a “local” anesthetic, which means that it works to numb only a small and focused region, as opposed to the whole-body numbness brought on by general anesthesia. Our first mistake of the following comedy of horrors that was supposed to masquerade as medicine, however, was to overestimate just how local “local” was, when it came to lidocaine. Lidocaine, it turns out, should be applied directly to the wounded area. Not even near it, directly to it. Not having prior experience with lidocaine, we decided to use it in an attempt to numb the man’s entire arm, from his elbow to fingertips. This, we thought, would probably be the most comfortable option for him. I proceeded to inject an amount of lidocaine that I suspected was more than enough in an attempt to avoid giving too little, in various places all over the man’s lower arm. Reasoning that anesthesia worked by blocking nerves, I hoped to spread enough around his arm that most, if not all nerves in it should be blocked. Alas, lidocaine does not travel throughout the body’s tissues as I had hoped, a fact made evident when I began suturing.

The first stitch, in keeping with the general theme of the rest of the night, did not go entirely as planned. The cut was already rather jagged and as much as possible, I didn’t want to make it worse. With this in mind, I placed the first stitch as close as I could to the border of the cut. I wove the thread through the flesh on the other side of the gash, again keeping it nice and close to the border. When I then pulled the stitch tight to tie it off, I witnessed the thread simply pull straight through the ragged flesh on both sides, leaving me kneeling on the sand, holding a bloody thread with a pair of forceps while a man with a burlap sack over his head shook in the darkness, repeating the phrase, “no mister, no, please”. It was hardly a calming moment.

Adding to everyone’s anxiety, the guard thumped the prisoner-cum-patient in the back with his rifle stock and instructed him to be quiet. Under the gaze of Armstrong and the guard and in the face (so to speak) of the prisoner, I returned to making the first stitch with as cool a demeanor as I could muster. This time, I placed the thread far enough back from the edge of the ragged cut, that it didn’t pull through. I was hardly out of the woods with this stitch, however, as I now had to tie it in a knot that would hold. I vaguely remembered being shown a special knot that would hold fast and could be tied using the sterile forceps I held in each hand. I stared at those two ends of the thread and willed more memories of that class to come forth, but the best I could manage was that there was something about two loops. After fumbling repeatedly with trying to make loops and chase thread ends through them using those stupid forceps, I finally managed to tie a square knot. It felt as much a victory as it did a defeat. I proceeded to the next stitch. This was a bad idea, but there was nothing to do now but keep going.

The needle sunk through thick skin to the soundtrack of “No, mister, please, no more,” and “Shut up! Be quiet!” At some point, I pulled another thread through and had to try again. No mister, please, mister! Another square knot. One more stitch. Mister please! Shut up! Thump goes the rifle’s stock. I’ve placed two of the sutures too far apart. As I tie one off, I can see one side of the gash folding to conform to my unnatural sewing line. Cut that stitch, try again. Please, mister! Just one more, I say. No more, mister, please! Hey, has he done this before, the guard asks. Armstrong, arms crossed, his face an expression of bored confidence, says oh yeah, hundreds of times. He’s the best, it’s just a difficult cut. One more stitch, ok? No more, mister! Ok, just one more. No, mister, please! Ok, really just one more this time. Mister, no!

Finally, the last stitch. Ok, done; no more. Oh, thank you mister, thank you! By now, he was swaying on his knees, regardless of any action taken by the guard. A cold sweat had soaked through every layer of my uniform, making the chill of the desert night all the more biting. Armstrong and I cleaned up our used medical supplies and made our way back to our ambulance. Under the guard’s supervision, the prisoner stumbled away towards his next trial, whatever it might have been. I felt that I had done some of the interrogator’s work, softening up the prisoner for questioning. I suppose that we had gotten the job done, although I couldn’t bring myself to take any comfort in such a thought.

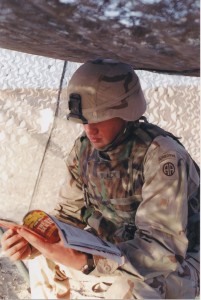

Being shown how to do stitches the right way.

I suppose that the episode made too good a story not to tell and so it made its way back to my base and into the ears of our surgeon. If this story is to have any silver lining, it is that our surgeon, shocked by the tale of our misadventure, paid exceptional attention to training me in proper suturing techniques. I became her go-to guy for doing stitches. Regardless of the hour, or whose shift it might be, if sutures were needed I would be summoned, perhaps awoken, to perform them. By the end of our deployment, I was an expert.

—Edit—

I spent three days at the detention camp.