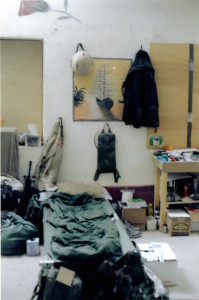

Most of my nine months in Iraq were spent on our base, a former Iraqi air force base called al-Taqqadum, or TQ for short. TQ was an abandoned Iraqi Air Force base originally built by the RAF after WWII. It already looked appropriately apocalyptic when we arrived. The base was spread out over a large area and consisted of a number of low, rectangular buildings and a few fortified Nissen huts, built to house aircraft. Entering TQ felt like setting foot in a ghost town. Few of the rectangular buildings still had doors and many of them had walls in various states of disrepair. By the time we arrived, the sand was already reclaiming what was once its own and half buried underneath it lay all manner of military detritus. Sun-baked boots, a helmet, scraps of uniform clothing and paperwork. So much paperwork full of the meaningless details out of which emerge the stories of a soldier’s time in service. These stories fluttered in the desert breezes, languished under the weight of sand, slept in battered metal cabinets and were finally swept away by us, erased and written over by our own stories. Our first tasks there consisted of cleaning and repairing the base.

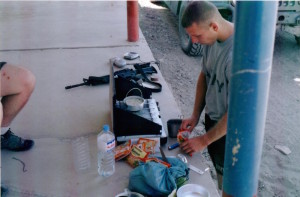

After completing most repairs and building whatever new structures we needed, our lives settled into a routine. This routine consisted of a cycle of two consecutive 24hr shifts of being on call for ambulance duty, with one shift spent being first on-call and the second being backup for the other team. This was followed by a “day” off, then running a convoy and having another “day” off. Repeat. The days off were theoretically a full 24 hours, but this never turned out to be the case. We considered a stretch of 16 hours, counting sleep, as a solid day off. It was a zombifying schedule. I don’t know how exactly many convoys I participated in, but at roughly 2 convoys per week for approximately 32 weeks (no regular convoys during our first month) and rounding down, since sometimes we would take part in a longer convoy, which meant that we only rode in one for that week, I estimate that it was close to 60. Most of those convoys blend together in my mind, becoming a grab-bag of snapshots from dusty nighttime roads with little sense of chronological order. Only a few stand out.

I read a lot during my time there. I easily read more in the nine months I served overseas than I did throughout all four years of high school. Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamozov, The Seven Pillars of

Wisdom, East of Eden and more. We played a lot of Risk, which seems strangely appropriate for a bunch of soldiers at war. Most of the guys played card games, but I’ve never really cared for those. I just read more instead. I tried keeping a journal, but that was a short-lived effort. Our favorite game was probably that of trying to push our buddys’ buttons, to test the limits of their good humor.

Some days, I pulled a shift on perimeter security and whiled away the hours playing backgammon, another of our favorite pastimes, with my companion while gazing at the fishermen, alone in their rowboats, upon the water. Guard duty is boring and I constantly envied the fishermen. The sunsets over the lake were like nothing I had ever seen, nor have ever seen elsewhere. Red and gold, but deeper and richer shades than I had ever seen before. The fading light would cast black shadows that stood out in sharp contrast to the golden-brown and red hues of the enveloping sand. At night, we continued to play backgammon with the help of our night vision goggles.

Thursdays in TQ were the worst because Thursday meant steak & lobster night at the dining facility, or DFAC.

Like anyone else, the first mention of steak & lobster dinners tricked us into thinking that this would be something to look forward to, a reward of sorts for all our labor. We quickly adopted the view that the weekly horror-fest was some sort of food disposal scam by KBR, the company responsible for our food and for the DFAC personnel, mostly private contractors from the Philippines. Both of the featured meats were of a dubious consistency. We could eat the steak easily with a spoon, the ‘meat’ caving to the inappropriate utensil’s slight pressure in a way that reminded me too much of paté. The lobster lay at the other end of the spectrum, potentially capable of doubling as emergency body armor. To make a point of it, one soldier tried stabbing the lobster (shell off, obviously) with his field knife. He might as well have punched a basketball. For some of us, Thursday nights became Top ramen and Snickers nights.

I drift to sleep in my cot, listening to the muezzin in the distance, calling the faithful to prayer. Closer, competing for volume, I hear the thumping sounds of the baptists shouting and dancing through their nightly rumpus. I’ve completed another chapter of Seven Pillars of Wisdom and I feel like in learning something of how Iraq was created, I’ve expanded my own experience of Iraq just that much more. Out of the darkness, Dustan says ‘hey dude, when we get back, can I date your sister?’ I reply ‘when we get back, can I date your mom?’ Five minutes of commentary about hot family members ensues, the entire platoon chiming in. We are children.